Collaboration For Watershed Conservation In Nepal

By Chris Holt, with contributions from Pushkar Khanal

Ina remote corner of western Nepal’s Dang District, Pateshwori Chaudhary is working to save the fish that live in the Rapti River. Pollution, destructive fishing practices, and poaching of the surrounding wildlife threaten the river’s biodiversity and cultural traditions.

Chaudhary is a member of the indigenous Tharu community, for whom fishing has been an important part of life for generations. Not long ago, Chaudhary himself fished using electric current or explosive devices (a practice known as “blast fishing”), a highly destructive fishing practice that destroys fish habitat and kills all fish indiscriminately regardless of size. This type of fishing provided Chaudhary and other men in his community a regular source of income — until the fish started to run out.

“I realized that fishing in such ways would create fatal consequences and generations after us would curse us for depriving them of experiencing the aquatic biodiversity in our rivers,” he said.

Protecting Aquatic Biodiversity

Chaudhary’s story is common among fishing communities in western Nepal, where the Karnali, Mahakali, and Rapti rivers provide a critical habitat for freshwater species, irrigate farmland, and propel hydroelectric dams. Water is the single most important natural resource underpinning Nepal’s economy and livelihoods, yet it faces increasing stress from population growth, climate change, and unregulated use.

The USAID Program for Aquatic Natural Resources Improvement, known locally as Paani (meaning “water” in Nepali), is helping change how local communities manage water resources in 12 priority watersheds, which span over 8,700 square kilometers of important habitat in the Karnali, Mahakali, and Rapti river basins. The five-year (2016–2020) activity complements and balances USAID/Nepal’s concurrent efforts to promote terrestrial biodiversity, fight deforestation, increase agriculture production, develop sustainable hydropower, and supports broader USAID goals to ensure the sustainability and therefore economic livelihoods and eventual self-reliance of these communities.

Aquatic biodiversity in Nepal is under increasing stress from factors such as hydropower, population growth, and irrigation needs. (Left) A hydropower site on the Dwari River, Dailekh District. Photo credit: Bhaskar Bhattarai/USAID. (Center) A new road and settlement construction along the Karnali River. Photo credit: Olaf Zerbock/USAID. (Right) Water being diverted for agriculture on the Babai River. Photo credit: Olaf Zerbock/USAID

“Paani promotes the idea that aquatic biodiversity is essential for healthy river systems. It complements the terrestrial biodiversity conservation activities we support by generating quality scientific data, developing community capacity for resource management, and improving governance of river basins and watersheds,” said USAID/Nepal Environment/Natural Resources Management Officer Chris Dege.

Enlisting Citizen Scientists

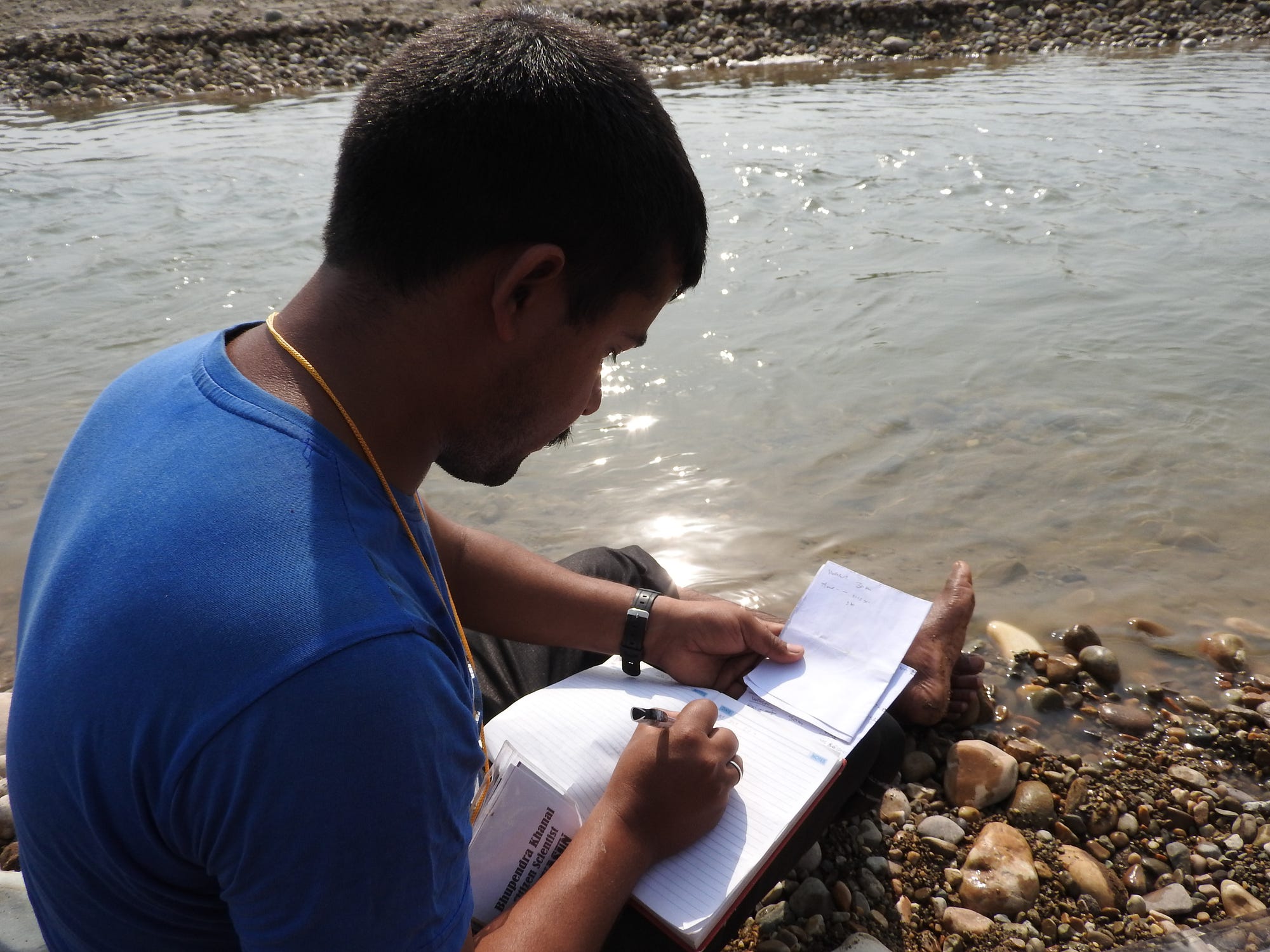

A citizen scientist tests water quality. Photo credit: USAID/Nepal

Paani aims to improve the knowledge-base around effective watershed management principles and basin-level planning to better inform national-level policymaking. To accomplish this, Paani first developed baseline assessments of the environmental health of 12 target watersheds. Working with local research organizations, Paani assessed a wide range of indicators, including water quality, soil fertility, and river bank land use. These findings were combined with qualitative assessments of watershed governance and equity, and helped Paani identify the most vulnerable segments of the river. This was a challenging process according to Paani Project Director Nilu Basnyat.

“We realized that the vast amount of information that is required to create profiles of watershed health were missing. The government doesn’t have consistent data across the basins, and flow data for the rivers was not regularly collected,” she explained. “The type of [water quality] data required to analyze watershed health was also not available.”

Early in the activity, Paani partnered with key civil society groups that have a vested interest in collecting and using such data. These umbrella organizations and their respective networks represent and advocate for water users, forest users, and traditionally underrepresented watershed stakeholders such as women, indigenous groups, and the Dalit people, a historically marginalized group at the bottom of the Nepalese social structure.

Paani mobilized members of these networks and trained them as “citizen scientists” to analyze water quality and provide household survey data using handheld mobiles and Android applications, with some participating in aquatic resource mapping exercises.

From Research to Policy

Pateshwori Chaudary (right) and other community stakeholders inspect some of their fishing areas on the Rapti River. Photo credit: Ram Moti Chaudhary/HWEPC

Paani is helping fishing communities conserve freshwater biodiversity and implement sustainable water management practices in the 12 priority watersheds. To do this, Paani is partnering with local NGOs such as the Human Welfare and Environment Protection Center (HWEPC) in Dang District. The organization works with rural municipalities in the Middle Rapti watershed to form community fishing groups that empower local stakeholders to protect their aquatic resources. In Rapti Rural Municipality, HWEPC helped form the 21-member Baikha fishing group, with Pateshwori Chaudhary as chairperson.

HWEPC and the Baikha fishing group put the citizen scientist concept into practice in the Rapti River, where they captured, measured, and photographed fish from their main fishing areas. The group created an aquatic animal catalog to help prioritize habitat protection for select fish species and control overfishing during breeding seasons. The catalog also serves as a reference to educate local communities on the importance of aquatic biodiversity conservation and highlights the potential of ecotourism to improve livelihoods.

Paani is training citizen scientists in Nepal to catalog fish species in their native habitats, like this one in the Karnali River. Photo credit: Satyam Joshi/USAID

The data HWEPC and the Baikha fishing group gathered, along with their promotional campaigns, garnered support from local government officials who committed public funding in the upcoming budget to support the Baikha fishing group. This local funding provides a sustainable solution to watershed conservation efforts after the Paani program ends.

Starting a Dialogue

In August 2018, community members and local government representatives from Middle Rapti watershed gathered for a town hall meeting to discuss concerns surrounding the declining health of the Rapti River. Attendees included Dhankumari Chaudhary from Gadhawa Rural Municipality, who voiced frustration over the lack of enforcement of existing bans on destructive fishing practices. “We initiated a [fish] conservation group in the village, trying to stop such destructive activities,” she said, “but the lack of strict laws against such acts has made it difficult for our group to stop such practices and encourage sustainable practices.”

This meeting, and subsequent advocacy work by Paani, set in motion the process of developing an Aquatic Animals and Biodiversity Conservation Bill for the Middle Rapti watershed, which Rapti Rural Municipality endorsed in February 2019. The bill includes a provision to hand over a 10 kilometer stretch of the Rapti River to the local community for management and protection. It is based on a legal framework for watershed protection that can be adapted to each municipality and is playing a key role in helping Paani achieve one of its ultimate goals — strengthening the ability of local governments to manage their own water resources.

Fisherman Sebak Kumal casts his net in the Rapti River, Middle Rapti Watershed. Photo credit: Manoj Chaudary/USAID Paani Program

As the result of collective advocacy, educational events, and dialogue with multiple stakeholders, similar bills have been passed or are under review in neighboring Rajpur Rural Municipality and Lamahi Municipality, along with several others in the Middle Karnali watershed, whose respective municipalities passed an Aquatic Animals and Biodiversity Conservation Bill in June 2018. So far, Paani has supported the implementation of an Aquatic Animals and Biodiversity Conservation Bill in eight municipalities.

These successes illustrate the importance of community engagement, social inclusion, open communication, and cooperation in achieving Paani’s goals. Moving forward, the program will continue to collaborate with all relevant stakeholders. The process is well underway in the 12 priority watersheds, according to Basnyat. “We have the policy, the governance, community mobilization, [and] communities strengthening and collaborating together to reduce negative environmental trends and pressures on the river systems,” she said.

For his part, Pateshwori Chaudhary is already seeing progress in the Middle Rapti watershed, where destructive fishing practices have largely halted and the community is reporting increased catches. After the monsoon season, Paani will conduct follow-up assessments to determine the extent to which fish stocks are starting to recover. Perhaps the most impressive — and important — change comes from people like Chaudhary, who once contributed to the watershed’s decline and now work to preserve it. “USAID’s Paani and HWEPC have helped [fulfill] my desire of conservation,” he said.

By Chris Holt, with contributions from Pushkar Khanal, Communications Officer for USAID’s Paani